The Saddest Tweet of Them All

Updated May 30, 2011--and again June 1

I've been watching as UW Madison moves into the post-NBP phase of life (wait, there is life after NBP?). In particularly, I'm finding the (re)framing of recent events by NBP proponents both fascinating, and disturbing.

Spin is, to some degree, expected. We can't blame Chancellor Martin for trying to save face, or Governor Walker for that matter.

What I didn't expect, and what upsets me most, is the self-righteousness evident in those who proclaim "we accomplished something here." Something, they claim, UW System did not. Could not. Would not.

Sad and short-sighted, perhaps, but not surprising. On the other hand, a recent tweet from a Madison student stopped me in my tracks. On Saturday he wrote, "No #UWNBP. Disappointing. Looks like we have to be tied to the poor decisions #UWSystem makes." Surprised at his statement, I responded, "Ever been to System? Ever met anyone there? Why do you follow blindly what u r told? #UWNBP #UWSystem." To which he replied "It's fun to make assumptions."

Well, that's sorta what I figured-- the majority of people claiming failure on the part of UW System and lauding the achievements of Chancellor Martin have never interacted with System. It's not that System is perfect -- far from it. But by degrading the capabilities of the governing body of our sister institutions, one casts dispersions on the quality of education received by other students. It's incredibly unproductive. It's also unfair. Of course, maybe people just don't care. I worried about that, so I wrote: "Fun, but destructive to students at other universities."

A moment later, I got a reply: "It isn't my job to be concerned with students at other universities." And a few minutes after that, he added: "It was my job to maximize my education and the value of this university, if that benefits other universities too, great!"

It was like a punch in the gut, as I suddenly realized that the whole UWNBP situation is but a microcosm of the broader threat to public education.

Too many of our fellow Americans are downright compassionless.

As David Berliner wrote in The Manufactured Crisis, "true improvements in public education will not come about unless they are based on compassion...If we structure our public school system so that large groups of students are not provided equitable education, we create a host of problems....In Lincoln's words, it has always been clear that effective reform of education must begin 'with charity for all.'"

None other than David Brooks makes a similar statement in today's New York Times, where he loudly admonishes college graduates "It's not about you." The big mistake society has made is giving undergraduates the impression the goal in life is to find themselves. Not hardly. The goal is to "lose yourself", Brooks explain, by "look[ing] outside and find[ing] a problem, which summons [your] life."

I guess we can't really blame the students. After all, they are simply following the example set by people like the alumni backing The Badger Advocates. Given that I've already publicly called them "goons" I suppose it's worth the risk to go one step further and say straight up that their latest press release reveals them as plain ol' liars. Yes, I said that. They are lying. Take a look. According to their revised version of reality, Chancellor Martin spent the last year attempting to "educate" the state about the need for the New Badger Partnership (if by educate you mean tell people the version of the facts you prefer, alrighty then), working "closely and diligently" with the Legislature while UW System "fought the proposal," worked "hastily," opposed "real reform," and basically did whatever was possible to undermine the thoughtful, hard work of Martin. "And although Martin worked tirelessly on the NBP, at the end of the year-long tour, she is respectful and considerate of the Joint Finance Committee and the Legislature’s desire to draft their own plan for UW-Madison and the system." There are no words for the extent to which this is a lie, other than COME ON! (I'm not alone in saying this.) The only truth in the whole darned thing is that Martin was on a "year-long tour."

We have been sold a bill of goods-- one that paints UW Madison into a corner as an elitist, know-it-all flagship that bears no resemblance to the rest of the state. We at UW Madison should be furious that anyone--anyone--is spending money "on our behalf" to support the kinds of work The Badger Advocates are doing. That they are doing it at the behest of our leader is even more appalling. At this point, they are more than undermining our credibility with the Legislature, in fact they threaten to further smear the good name of Madison in the hearts and minds of the rest of Wisconsin. Not only have they -- and she-- not given up on Public Authority, they are pushing harder.

This state faces massive inequities in the provision of both k-12 and higher education. If we at UW-Madison cannot teach our undergraduates compassion for their fellow undergraduates-- at all public institutions throughout the state-- then we are doomed to a competitive race to the bottom. If the only route they can see to helping others is by helping themselves, we have not done our jobs.

That was the lesson I got from Twitter that day. We have failed to educate. We must do more.

The Truth About the Proposed NBP: LFB Weighs In

The New Badger Partnership is -- reportedly-- dead. In the meantime, the Legislative Fiscal Bureau has just released its analysis of what Public Authority would look like if the NBP were passed. The report is quite interesting, and in particular I think the following points are worth highlighting:

(1) Despite the Chancellor's claims that what she wanted was "part of a national trend" the governance structure Madison asked for was quite unusual, when considering arrangements in other states.

"Attachment 1 provides an overview of the governance structures of institutions that are similar to UW-Madison in terms of size and federal research and development funding. These institutions are all public or "state-related" institutions with large student populations, high six-year graduation rates, and federal research and development expenditures above $400 million in 2008-09. As shown in the Attachment, these institutions have a variety different governance structures. Of the institutions shown, the University of Michigan, the University of Washington, and the University of Pittsburgh have governance structures most similar to that proposed for UW-Madison under the bill. Each of these institutions is governed by a board that oversees that institution and a limited number of smaller regional institutions. However, in Michigan and Washington, most other public four-year institutions similarly have their own governing board. In Pennsylvania, there are separate governing boards for Pennsylvania State University, the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, Temple University, and Lincoln University. None of the states shown have one governing board for the flagship institution and one governing board for all other public higher education institutions as Wisconsin would under the bill."

(2) Madison's claims that it has suffered disproportionate losses over time in the race for funding and that it especially needs these flexibilities-- or at least, it should get them NOW before other schools-- seems quite off considering these facts:

"When adjusted for inflation, state funding provided for UW-Madison and for all other UW System institutions decreased from 1990-91 to 2010-11. Over that period of time, state funding for UW-Madison decreased by 2.8% while state funding for all other UW System institutions decreased by 6.8%. At the same time, enrollment at UW-Madison increased by 1.5% while enrollments at all other UW System institutions increased by 23.4%. When these increases in enrollment are controlled for, state funding for UW-Madison decreased by 4.2% while state funding for all other UW System institutions decreased by 24.4%. Given that state funding for UW System institutions other than UW-Madison have decreased by a greater amount than state funding for UW-Madison over the past twenty years, it is unclear whether UW-Madison or the other UW System institution would benefit most in terms of state funding if UW-Madison were no longer part of the UW System."

"Salaries at UW-Milwaukee and the comprehensives are significantly farther behind their peers than salaries at UW-Madison are. For this reason, the Committee may want to extend any compensation flexibilities that may be provided to UW-Madison to all UW institutions."

(3) Madison's claims about the monetary savings from NBP appear to be over-stated.

"..As an authority, UW-Madison would not be required to deposit most of its program revenues or any of its federal revenues in the state treasury. The UW-Madison Chancellor has asserted that keeping these accounts separate from other state moneys would protect these funds from being transferred to support other state programs as has occurred in the past. In the Wisconsin Idea Partnership, the UW System Board of Regents similarly proposes that most of its program revenues and all of its federal revenues similarly be kept outside of the state treasury. The UWMadison Chancellor contends that the UW System, which would remain a state agency, would not be able to deposit these revenues outside of the state treasury leaving them susceptible to transfers. However, the cash management policies proposed for the UW-Madison authority may not fully protect these funds from future transfers, either. Regardless of where UW-Madison authority funds are deposited, it appears that as a matter of law, the Legislature could compel UW-Madison, as an authority created by state statute, to transfer funds to the state at any time."

(4) There was significant potential for tuition to skyrocket in order to increase faculty salaries.

"Under current practice, many UW faculty and academic staff positions are funded through a combination of state GPR and tuition. Compensation plans approved by the Joint Committee on Employment Relations (JCOER) therefore include a GPR portion and a tuition portion. If the UW Board of Regents or the proposed UW-Madison authority Board of Trustees were provided both unlimited tuition authority and the ability to approve pay plans for faculty, academic staff, and senior executives, the Legislature would not be able to limit the amount by which resident undergraduate tuition would be increased to fund those pay plans."

(5) Tying tuition increases to accountability for increasing financial aid was an option-- but not one Madison proposed.

"A third option could be to grant the Board of Trustees and the Board of Regents full authority to set tuition rates but to require them to report to the Legislature on certain specified measures such as the number of low-income students enrolled, retention and graduation rates for low-income students, and the amount of need-based financial aid provided through federal, state, and institutional programs. The Legislature could set goals for the UW-Madison authority or the UW System and could penalize the institution or institutions, either by reducing GPR funding or limiting tuition authority, if sufficient progress towards those goals is not met."

Good thing this bad idea has been recognized for what it truly was. A mess.

(1) Despite the Chancellor's claims that what she wanted was "part of a national trend" the governance structure Madison asked for was quite unusual, when considering arrangements in other states.

"Attachment 1 provides an overview of the governance structures of institutions that are similar to UW-Madison in terms of size and federal research and development funding. These institutions are all public or "state-related" institutions with large student populations, high six-year graduation rates, and federal research and development expenditures above $400 million in 2008-09. As shown in the Attachment, these institutions have a variety different governance structures. Of the institutions shown, the University of Michigan, the University of Washington, and the University of Pittsburgh have governance structures most similar to that proposed for UW-Madison under the bill. Each of these institutions is governed by a board that oversees that institution and a limited number of smaller regional institutions. However, in Michigan and Washington, most other public four-year institutions similarly have their own governing board. In Pennsylvania, there are separate governing boards for Pennsylvania State University, the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, Temple University, and Lincoln University. None of the states shown have one governing board for the flagship institution and one governing board for all other public higher education institutions as Wisconsin would under the bill."

(2) Madison's claims that it has suffered disproportionate losses over time in the race for funding and that it especially needs these flexibilities-- or at least, it should get them NOW before other schools-- seems quite off considering these facts:

"When adjusted for inflation, state funding provided for UW-Madison and for all other UW System institutions decreased from 1990-91 to 2010-11. Over that period of time, state funding for UW-Madison decreased by 2.8% while state funding for all other UW System institutions decreased by 6.8%. At the same time, enrollment at UW-Madison increased by 1.5% while enrollments at all other UW System institutions increased by 23.4%. When these increases in enrollment are controlled for, state funding for UW-Madison decreased by 4.2% while state funding for all other UW System institutions decreased by 24.4%. Given that state funding for UW System institutions other than UW-Madison have decreased by a greater amount than state funding for UW-Madison over the past twenty years, it is unclear whether UW-Madison or the other UW System institution would benefit most in terms of state funding if UW-Madison were no longer part of the UW System."

"Salaries at UW-Milwaukee and the comprehensives are significantly farther behind their peers than salaries at UW-Madison are. For this reason, the Committee may want to extend any compensation flexibilities that may be provided to UW-Madison to all UW institutions."

(3) Madison's claims about the monetary savings from NBP appear to be over-stated.

"..As an authority, UW-Madison would not be required to deposit most of its program revenues or any of its federal revenues in the state treasury. The UW-Madison Chancellor has asserted that keeping these accounts separate from other state moneys would protect these funds from being transferred to support other state programs as has occurred in the past. In the Wisconsin Idea Partnership, the UW System Board of Regents similarly proposes that most of its program revenues and all of its federal revenues similarly be kept outside of the state treasury. The UWMadison Chancellor contends that the UW System, which would remain a state agency, would not be able to deposit these revenues outside of the state treasury leaving them susceptible to transfers. However, the cash management policies proposed for the UW-Madison authority may not fully protect these funds from future transfers, either. Regardless of where UW-Madison authority funds are deposited, it appears that as a matter of law, the Legislature could compel UW-Madison, as an authority created by state statute, to transfer funds to the state at any time."

(4) There was significant potential for tuition to skyrocket in order to increase faculty salaries.

"Under current practice, many UW faculty and academic staff positions are funded through a combination of state GPR and tuition. Compensation plans approved by the Joint Committee on Employment Relations (JCOER) therefore include a GPR portion and a tuition portion. If the UW Board of Regents or the proposed UW-Madison authority Board of Trustees were provided both unlimited tuition authority and the ability to approve pay plans for faculty, academic staff, and senior executives, the Legislature would not be able to limit the amount by which resident undergraduate tuition would be increased to fund those pay plans."

(5) Tying tuition increases to accountability for increasing financial aid was an option-- but not one Madison proposed.

"A third option could be to grant the Board of Trustees and the Board of Regents full authority to set tuition rates but to require them to report to the Legislature on certain specified measures such as the number of low-income students enrolled, retention and graduation rates for low-income students, and the amount of need-based financial aid provided through federal, state, and institutional programs. The Legislature could set goals for the UW-Madison authority or the UW System and could penalize the institution or institutions, either by reducing GPR funding or limiting tuition authority, if sufficient progress towards those goals is not met."

Good thing this bad idea has been recognized for what it truly was. A mess.

A Provocative New Report on Higher Education

I know we in Wisconsin are sick and tired of hearing about Virginia....but please bear with me, because a new report out of UVA will likely resonate-- especially with my UW-Madison readers.

A new Lumina Foundation-funded report from the Miller Center and the Association of Governing Boards of Colleges and Universities, based on a December 2010 meeting about "how to maximize higher education’s contributions to the American economy" makes the following provocative statement:

The past few decades have seen far too many colleges and universities engage in a rush toward elite status. The more selective an institution is, the better. The more research money it collects, the better. The higher it ranks in national and international publications, the better. But what has the race for status contributed to the public good? It is possible to build state institutions that are noted in U.S. News & World Report and national rankings of research universities but ignore the needs of many or most of a state’s people.

Among the report's recommendations:

(1) Rethink the purpose and functions of governing boards (e.g. like our Board of Regents). Give them new leadership roles, including setting clear goals for their member institutions and creating funding mechanisms linked to these goals. "The state governing and coordinating boards are still needed, both for their leadership and for the “buffer” role that they play between higher education institutions and state governments...In addition to measuring and paying for performance, state boards should encourage institutional redesign, curriculum revision, and the introduction of educational programs.. that meet the needs of new kinds of students...State boards should promote review of the missions of institutions,and create conditions in which it is in their own best interests to focus on the public mission of higher education...Reconsidering the missions of colleges and universities requires participation by faculty, institutional management, institutional governing bodies, and those who are responsible for the statewide coherence of higher education. It also requires consultation with the executive and legislative branches of government, with employers, localities, and the business community in general."

(2) Assign greater percentages of [institutional] operating budgets to instruction in order to achieve higher rates of degree completion. "The percentage of increases in student tuition over the past several years is far greater than the increases in expenditures on instruction. Where is the money going? What expenditures can be reduced or eliminated?...Many institutions have grown used to spending their money on things that may not reflect the needs of the states or regions that they are supposed to serve."

(3) Increase faculty teaching responsibilities. "Reduce the number of non-permanent and adjunct faculty -- this almost certainly will require that many regular, full-time faculty members teach more courses and be relieved of other duties for which they have volunteeredor to which they have been assigned."

(4) Restrict research efforts to a limited number of institutions. "..Say clearly that the “research” obligation of the great majority of faculty members is simply to remain current in their fields. Relatively few of them are going to make historic contributions to human knowledge."

(5) Adopt tighter, more focused curricula with key learning objectives."..The “electives” that have proliferated in the past half-century often are far less cost-effective, in part because enrollment in them is voluntary and usually smaller, and not required for particular programs of study. A core curriculum of required courses may seem less attractive than a wide array of choices, but it also may be less costly and more focused on key learning objectives. It is also likely to lead to higher levels of program completion."

(6) "Institutions should be required to assess what students learn and to measure and report their progress in clear and unambiguous terms."

Now, I don't agree with every idea in here-- but I do think this is a very useful report for framing a discussion about the future of Wisconsin public higher education, and I urge you to review it in full.

A new Lumina Foundation-funded report from the Miller Center and the Association of Governing Boards of Colleges and Universities, based on a December 2010 meeting about "how to maximize higher education’s contributions to the American economy" makes the following provocative statement:

The past few decades have seen far too many colleges and universities engage in a rush toward elite status. The more selective an institution is, the better. The more research money it collects, the better. The higher it ranks in national and international publications, the better. But what has the race for status contributed to the public good? It is possible to build state institutions that are noted in U.S. News & World Report and national rankings of research universities but ignore the needs of many or most of a state’s people.

Among the report's recommendations:

(1) Rethink the purpose and functions of governing boards (e.g. like our Board of Regents). Give them new leadership roles, including setting clear goals for their member institutions and creating funding mechanisms linked to these goals. "The state governing and coordinating boards are still needed, both for their leadership and for the “buffer” role that they play between higher education institutions and state governments...In addition to measuring and paying for performance, state boards should encourage institutional redesign, curriculum revision, and the introduction of educational programs.. that meet the needs of new kinds of students...State boards should promote review of the missions of institutions,and create conditions in which it is in their own best interests to focus on the public mission of higher education...Reconsidering the missions of colleges and universities requires participation by faculty, institutional management, institutional governing bodies, and those who are responsible for the statewide coherence of higher education. It also requires consultation with the executive and legislative branches of government, with employers, localities, and the business community in general."

(2) Assign greater percentages of [institutional] operating budgets to instruction in order to achieve higher rates of degree completion. "The percentage of increases in student tuition over the past several years is far greater than the increases in expenditures on instruction. Where is the money going? What expenditures can be reduced or eliminated?...Many institutions have grown used to spending their money on things that may not reflect the needs of the states or regions that they are supposed to serve."

(3) Increase faculty teaching responsibilities. "Reduce the number of non-permanent and adjunct faculty -- this almost certainly will require that many regular, full-time faculty members teach more courses and be relieved of other duties for which they have volunteeredor to which they have been assigned."

(4) Restrict research efforts to a limited number of institutions. "..Say clearly that the “research” obligation of the great majority of faculty members is simply to remain current in their fields. Relatively few of them are going to make historic contributions to human knowledge."

(5) Adopt tighter, more focused curricula with key learning objectives."..The “electives” that have proliferated in the past half-century often are far less cost-effective, in part because enrollment in them is voluntary and usually smaller, and not required for particular programs of study. A core curriculum of required courses may seem less attractive than a wide array of choices, but it also may be less costly and more focused on key learning objectives. It is also likely to lead to higher levels of program completion."

(6) "Institutions should be required to assess what students learn and to measure and report their progress in clear and unambiguous terms."

Now, I don't agree with every idea in here-- but I do think this is a very useful report for framing a discussion about the future of Wisconsin public higher education, and I urge you to review it in full.

Let the Sunshine In

Evidence-based decision-making requires data. We can disagree over the merits of using evidence to make decisions and we can also worry about the quality of the data collected, but if we hope to ground decisions in facts we need data.

As all higher education researchers know, there are enormous barriers that prevent the use of data in decision-making about program effectiveness. Think it's difficult to study the k-12 system? Come over to the dark side sometime, where de-centralized colleges and universities get to act independently when making decisions about granting data access, and nearly all find some convoluted way to hide behind FERPA.

Oh FERPA, that big hairy monster that claims to protect students' rights by shielding them from the benefits of evidence-based practices. Paying skyhigh tuition to your college while assuming they have ensured the way they teach actually "works"? Think again--- in all likelihood, the only people who've looked at the data are on the inside; administration-paid institutional researchers who are over-worked and underpaid, and most importantly tasked with responding to administrator whims and reporting requirements-- leaving little time for deep, thoughtful inquiry.

FERPA is very often used to deny external researchers access to student record data. Most often, we are simply told "Can't. FERPA doesn't allow it." "Oh that FERPA, that silly, silly FERPA. We WANT to give you the evidence we're doing a great job, but sorry, can't compromise student privacy."

Most of this is completely bogus, and thankfully the Data Quality Campaign has been working to reform FERPA, bringing it into the 21st century with all of its security protections. Back in April DQC had a big win, when the Department of Education released new proposed amendments to FERPA. The changes would "facilitate fuller access for research and evaluation purposes to student data contained in state longitudinal data systems (SLDSs) in order to increase accountability and transparency for educational outcomes and to contribute to a culture of innovation and continuous improvement in education, while at the same time enhancing privacy protections through expanded requirements for written agreements as the basis for disclosures of data and US ED enforcement mechanisms. They would authorize fuller, more cost effective use of state-level student data for research, evaluation, and accountability, subject to clear privacy protections, as well as effective use of data across all levels of education to evaluate and improve education programs."

Rock on! This was simply an excellent step.

Oh but wait-- here comes Dupont Circle. This morning, around 30 higher education associations released a letter objecting to the proposed regs. They are all for research, they say, but the privacy protections aren't strong enough.

Why am I not surprised? I hate to be so cynical, but if these associations really were supportive of the main reform goals, the letter could have begun with much stronger, clearer statements about the need for higher education to benefit from research-based practices, and denouncing the historical resistance to that culture. The privacy concerns could then be framed as necessary modifications to "make this work"-- instead, the letter comes off as weak whining at best, and typical platitudes about protecting student privacy at worst.

In recent years I've watched brave colleges and universities step up to facilitate external research and integrate it into their practices. The University of Wisconsin System and the Wisconsin Technical Colleges are among them. Let's hope their national associations get on board.

What Wisconsin Needs Now: Collective Efficacy

When citizens seek to solve social problems, they are much more effective if they work together rather than alone. This basic, sensible idea is also known as "collective efficacy." And it is what must be inculcated in Wisconsin residents if we are to preserve our world-class public higher education systems.

Our willingness to act, when needed, for one another's benefit, generates long-lasting effects. Unfortunately, there is a strong impulse to turn inward when threatened, to focus on self-preservation rather than community preservation.

Solutions for issues like the fiscal challenges facing the University of Wisconsin System will not emerge if we follow leaders with imperious styles who seek to "win" no matter what the cost. Regardless of the specific policy agenda, the process of policy formation is essential since it dictates the terms of the debate.

This may sound exceedingly feel-good, but it is also deeply pragmatic. The savings that will accrue to individual campuses from any "flexibilities" are small (numbers provided to me by Darrell Bazzell are in the $10-20 million range for Madison) but collectively (if granted to all campuses) fairly large. The same is true for proposed efficiencies such as adjustments in faculty/student ratio. If, as a community, UW System examined that key cost driver across departments and divisions throughout all institutions, it could reasonably begin to make assessments about resource distribution. I suspect that some departments at UW-Madison would actually see that ratio decreased as a result, perhaps because of resources saved at another campus-- and vice versa.

The climate at UW Madison has eroded dramatically over the course of several recent policy debates such as the Madison Initiative for Undergraduates, the Graduate School Restructuring, the Huron Engagement, and now the New Badger Partnership. Faculty, staff, and students are fearful of repercussions from both the success and/or the failure of the NBP. Rumors of the imminent departure of our friends and colleagues fly around daily. Motivation and productivity are down.

The way forward lies in refocusing on what has always made Madison -- and System -- great. That is: our commitment to a community that prioritizes fearless sifting and winnowing and shared decision-making to a degree uncommon in other institutions of higher education. That's the community and commitment that put us on the map. We have been through hard financial times before, and inevitably will go through them again. Stick to what we do best, and what we can do best no matter how many dollars we have at the moment, and we will shine.

Our willingness to act, when needed, for one another's benefit, generates long-lasting effects. Unfortunately, there is a strong impulse to turn inward when threatened, to focus on self-preservation rather than community preservation.

Solutions for issues like the fiscal challenges facing the University of Wisconsin System will not emerge if we follow leaders with imperious styles who seek to "win" no matter what the cost. Regardless of the specific policy agenda, the process of policy formation is essential since it dictates the terms of the debate.

This may sound exceedingly feel-good, but it is also deeply pragmatic. The savings that will accrue to individual campuses from any "flexibilities" are small (numbers provided to me by Darrell Bazzell are in the $10-20 million range for Madison) but collectively (if granted to all campuses) fairly large. The same is true for proposed efficiencies such as adjustments in faculty/student ratio. If, as a community, UW System examined that key cost driver across departments and divisions throughout all institutions, it could reasonably begin to make assessments about resource distribution. I suspect that some departments at UW-Madison would actually see that ratio decreased as a result, perhaps because of resources saved at another campus-- and vice versa.

The climate at UW Madison has eroded dramatically over the course of several recent policy debates such as the Madison Initiative for Undergraduates, the Graduate School Restructuring, the Huron Engagement, and now the New Badger Partnership. Faculty, staff, and students are fearful of repercussions from both the success and/or the failure of the NBP. Rumors of the imminent departure of our friends and colleagues fly around daily. Motivation and productivity are down.

The way forward lies in refocusing on what has always made Madison -- and System -- great. That is: our commitment to a community that prioritizes fearless sifting and winnowing and shared decision-making to a degree uncommon in other institutions of higher education. That's the community and commitment that put us on the map. We have been through hard financial times before, and inevitably will go through them again. Stick to what we do best, and what we can do best no matter how many dollars we have at the moment, and we will shine.

It's All About the Faculty: Update

On April 25 I blogged about the claim made by some NBP proponents that the policy change was needed in order to stem the tide of faculty turnover at UW-Madison. In that post I referred to some data from a 1999 report, which at the time was all I could locate on the web.

I have now had the opportunity to examine more recent data (UW-Madison faculty have access to it at the APA website) and here are some updates:

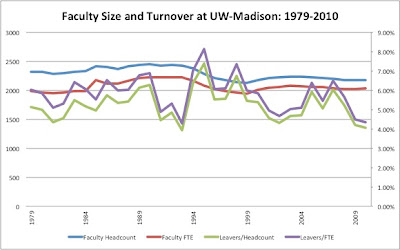

(1) In the prior post, I claimed that there hadn't been much change over time in turnover rates at Madison. As I said, I was looking at data up til 1999 and it showed a rate of about 5 or 6% (based on number of leavers divided by total number of faculty). The more recent data shows even lower turnover rates since that time-- no doubt due in large part to the efforts of UW Administration and the fact that the 2005-07, 2007-09 and 2009-11 biennial budgets provided High Demand Faculty Retention Funds (HDFRF) to address recruitment and retention issues. In the graph below, the blue and red lines show the number of faculty (blue is headcount and red is FTE) and green and purple show the turnover rate calculated two ways (green by dividing # leavers by headcount, and purple dividing #leavers by FTE). As you can see, there's no evidence that our turnover is climbing.

(2) The percent of our faculty receiving outside offers declined during the 1980s and 1990s (from a high of 7.7% in 1983 to a low of 2.4% in 1999) and then grew again during the 21st century to a high of 8.1% in 2009. However, after a steady decline in the 1990s, our success at retaining faculty who receive offers has increased from 60% in 2001 to 84% in 2008 and 80% in 2009.

(3) Probably due to the state support in this area, the percent of payroll devoted to these retention offers declined from up to 10% in the 1980s to barely 1% in 2009.

It certainly seems that those funds from the state helped stave off an uptick in faculty turnover rates. What isn't clear is that the NBP--and the Public Authority model in particular-- is necessary in order to continue to use funds in this manner. In 2009-2010 we spent less than $1.5 million on this effort.

I have now had the opportunity to examine more recent data (UW-Madison faculty have access to it at the APA website) and here are some updates:

(1) In the prior post, I claimed that there hadn't been much change over time in turnover rates at Madison. As I said, I was looking at data up til 1999 and it showed a rate of about 5 or 6% (based on number of leavers divided by total number of faculty). The more recent data shows even lower turnover rates since that time-- no doubt due in large part to the efforts of UW Administration and the fact that the 2005-07, 2007-09 and 2009-11 biennial budgets provided High Demand Faculty Retention Funds (HDFRF) to address recruitment and retention issues. In the graph below, the blue and red lines show the number of faculty (blue is headcount and red is FTE) and green and purple show the turnover rate calculated two ways (green by dividing # leavers by headcount, and purple dividing #leavers by FTE). As you can see, there's no evidence that our turnover is climbing.

(2) The percent of our faculty receiving outside offers declined during the 1980s and 1990s (from a high of 7.7% in 1983 to a low of 2.4% in 1999) and then grew again during the 21st century to a high of 8.1% in 2009. However, after a steady decline in the 1990s, our success at retaining faculty who receive offers has increased from 60% in 2001 to 84% in 2008 and 80% in 2009.

(3) Probably due to the state support in this area, the percent of payroll devoted to these retention offers declined from up to 10% in the 1980s to barely 1% in 2009.

It certainly seems that those funds from the state helped stave off an uptick in faculty turnover rates. What isn't clear is that the NBP--and the Public Authority model in particular-- is necessary in order to continue to use funds in this manner. In 2009-2010 we spent less than $1.5 million on this effort.

Is Our Students Learning?

Remarkably, one of the topic's of yesterday's blog post (and another I wrote two years ao)-- the limited learning taking place on many college campuses-- is the subject of a New York Times op-ed today. Titled, "Your So-Called Education," the piece argues that while 90% of graduates report being happy with their college experience, data suggests there's little to celebrate. I urge you read it and its companion op-ed "Major Delusions," which describes why college grads are delusional in their optimism about their future.

We don't regularly administer the Collegiate Learning Assessment at UW-Madison, the test that the authors of the first op-ed used to track changes in student learning over undergraduate careers. From talking with our vice provost for teaching and learning, Aaron Brower, I understand there are many good reasons for this. Among them are concerns that the test doesn't measure the learning we intend to transmit (for what it does measure, and how it measures it, see here), as well as concerns about the costs and heroics required to administer it well. In the meantime, Aaron is working on ways to introduce more high-impact learning practices, including freshmen interest groups and learning communities, and together with colleagues has written an assessment of students' self-reports of their learning (the Essential Learning Outcomes Questionnaire). We all have good reason to wish him well. For it's clear from what we do know about undergraduate learning on campus, we have work to do.

The reports contained in our most recent student engagement survey (the NSSE, administered in 2008) indicate the following:

1. Only 60% of seniors report that the quality of instruction in their lower division courses was good or excellent.

This is possibly linked to class size, since only 37% say that those classes are "ok" in size -- but (a) that isn't clear, since the % who says the classes are too large and the % that say they are too small are not reported, and (b) the question doesn't link class size to quality of instruction. As I've noted in prior posts, it's a popular proxy for quality but also one that is promoted by institutions since smaller classes equates with more resources (though high-quality instruction does not apparently equate with smaller classes nor high resources). There are other plausible explanations for the assessment of quality that the survey does not shed light on.

2. A substantial fraction of our students are not being asked to do the kind of challenging academic tasks associated with learning gains.

For example, 31% of seniors (and 40% of freshmen) report that they are not frequently asked to make "judgments about information, arguments, or methods, e.g., examining how others gathered/ interpreted data and assessing the soundness of their conclusions." (Sidebar-- interesting to think about how this has affected the debate over the NBP.) 28% of seniors say they are not frequently asked to synthesize and organize "ideas, information, or experiences into new, more complex interpretations and relationships." On the other hand, 63% of seniors and 76% of freshmen indicate that they are frequently asked to memorize facts and repeat them. And while there are some real positives-- such as the higher-than-average percent of students who feel the university emphasizes the need to spend time on academic work-- fully 45% of seniors surveyed did not agree that "most of the time, I have been challenged to do the very best I can."

3. As students get ready to graduate from Madison, many do not experience a rigorous academic year.

In their senior year, 55% of students did not write a paper or report of 20 pages or more, 75% read fewer than 5 books, 57% didn't make a class presentation, 51% didn't discuss their assignments or grades with their instructor, and 66% didn't discuss career plans with a faculty member or adviser. Nearly one-third admitted often coming to class unprepared. Less than one-third had a culminating experience such as a capstone course or thesis project.

4. The main benefit of being an undergraduate at a research university--getting to work on a professor's research project-- does not happen for the majority of students.

While 45% of freshmen say it is something they plan to do, only 32% of seniors say they've done it.

Yet overall, just as the Times reports, 91% of UW-Madison seniors say their "entire educational experience" was good or excellent.

Well-done. Now, let's do more.

Postscript: Since I've heard directly from readers seeking more resources on the topic of student learning, here are a few to get you started.

A new report just out indicates that college presidents are loathe to measure learning as a metric of college quality! Instead, they prefer to focus on labor market outcomes.

Measuring college learning responsibly: accountability in a new era by Richard J. Shavelson is a great companion to Academically Adrift. Shavelson was among the designers of the CLA and he responds to critics concerned with its value.

The Voluntary System of Accountability, embraced by public universities who hope to provide their own data rather than have a framework imposed on them. Here is Madison's report.

On the topic of students' own reports of their learning gains, Nick Bowman's research is particularly helpful. For example, in 2009 in the American Education Research Journal Bowman reported that that in a longitudinal study of 3,000 first year students, “across several cognitive and noncognitive outcomes, the correlations between self-reported and longitudinal gains are small or virtually zero, and regression analyses using these two forms of assessment yield divergent results.” In 2011, he reported in Educational Researcher that "although some significant differences by institutional type were identified, the findings do not support the use of self-reported gains as a proxy for longitudinal growth at any institution."

As for the NSSE data, such as what I cited above from UW-Madison, Ernie Pascarella and his colleagues report that these are decent at predicting educational outcomes. Specifically, “institution-level NSSE benchmark scores had a significant overall positive association with the seven liberal arts outcomes at the end of the first year of college, independent of differences across the 19 institutions in the average score of their entering student population on each outcome. The mean value of all the partial correlations…was .34, which had a very low probability (.001) of being due to chance."

Finally, you should also check out results from the Wabash study.

Making Opportunity Affordable

In recent days, an NBP proponent accused me of hoping to "McDonaldize" UW-Madison. He made this accusation because I dared suggest that the university is not operating as productively as it could be. Our per-pupil spending is lower than at many of our peers, and especially lower than privates, he says. Sure, that's true. But frankly, it's about as relevant as my son proclaiming that he should have two desserts after dinner just because other kids at preschool regularly have three or four! Mistakes made by other institutions don't justify our own. We can, and must, do better.

Lately our attention has been drawn to one particular trend in higher education-- the disinvestment of the state from higher education. Let me add to that three others: (1) time-to-degree is up at the majority of public colleges and universities, (2) socioeconomic gaps in college completion rates are stagnant, and (3) most students are not registering any learning gains over four years of college attendance.

So while students and their families are being asked to pay more for college, it seems like they aren't actually getting anything additional for their money. That means productivity is declining, pure and simple. The fact that a college degree still brings a large wage premium is nice, but that appears at least partly (or even largely) attributable to employers' willingness to accept a diploma as a proxy for learning. Too bad for many universities: researchers are blowing apart that assumption as we speak.

But fear not: improving productivity does not mean reducing quality. Anyone who claims otherwise is ignoring the latest learning science studies. And lest you think that I'm pushing an agenda that aims to demolish the traditional institutions in favor of for-profit models, well, ask around-- nothing could be further from the truth. I focus on enhancing productivity because making gains in this domain is truly the only politically viable way of making opportunity affordable.

High-caliber institutions like Carnegie Mellon are pursuing new ways to educate and support undergraduates that are more productive-- and thus more cost-effective-- than older models. Some colleges and universities feel threatened by this, and loudly proclaim their current practices "work" and are "cheaper." But the culture of evidence in higher education administration is notoriously weak, and thus program impacts are rarely if ever measured in meaningful ways. Absent an approach that considers impacts relative to costs, there's no basis for protecting "business-as-usual."

With that in mind, I'm going to begin to quickly highlight on this blog some key initiatives that appear to be cost-effective, highly impactful ways of educating the kinds of students like those UW-Madison serves. If the basic idea of each intrigues you, I'm giving you links to read more. My intent is to get a serious conversation started-- a conversation about refocusing on our core mission: providing a high-quality affordable education to the Wisconsin residents we serve. (We'd join many other states in this important conversation, for example read about Oregon.)

Initiative #1: Open Learning Initiative at Carnegie Mellon.

Students need effective instruction that incorporates regular assessment and supplements with tutoring as needed. Technology can assist professors in accomplishing this.

"OLI courses are developed by teams composed of faculty, learning scientists, human-computer interaction experts, and software engineers in order to make the best use of multidisciplinary knowledge for designing effective learning environments. The OLI design team articulates an initial set of student-centered, measurable learning objectives and designs the instructional environment to support students in achieving them.The instructional activities in OLI courses contain small amounts of explanatory text and many activities that capitalize on the computer's capability to display digital images and simulations and to promote interaction. Many of the courses also include virtual lab environments that encourage flexible and authentic exploration. Perhaps the most salient feature of OLI course design is the embedding of quasi-intelligent tutors—or “mini-tutors”—within the learning activities throughout the course... An intelligent tutor is a computerized learning environment whose design is based on cognitive principles and whose interaction with students is like those of a human tutor—making comments when students err, answering questions about what to do next, and maintaining a low profile when they are performing well. This approach differs from traditional computer-aided instruction, which gives didactic feedback to students on their final answers; the OLI tutors provide context-specific assistance throughout the problem-solving process."

Read more about OLI in a White House commissioned paper here.

Initiative #2: Inside Track

Persisting in college does not equate with making timely progress towards a degree, or even enjoying the academic experience at all. Mentoring can help. The Inside Track student coaching model assigns an executive coach to needy students, at a cost of just $500 for 6 months. It is an increasingly popular program at public universities, including Florida State. An extensive randomized evaluation indicates a 10-15 percentage point increase in retention rates.

POSTSCRIPT:

It's worth noting that UW-Madison has begun participating in the Delaware Study of Instructional Costs and Productivity. This allows us to benchmark instructional spending at the department level against those at other participating institutions (e.g. Ohio State University, SUNY - University at Buffalo, University of Arizona, University of Colorado - Boulder, University of Kansas, University of Missouri - Columbia , University of Nebraska - Lincoln, University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill, University of Oregon ,University of Texas at Austin). (These aren't the best comparisons but they are all that's given, and at least one of my readers is demanding comparisons no matter what.) The most recent year of our data indicates that our direct instructional expenditures per student credit hour are on the high side--not appalling high, but higher than average-- and importantly that there is widespread variation by discipline and department. Of possible concern are departments where the number of student credit hours per instructional faculty (e.g. the volume) is much lower than that of the comparison group of institutions, while the expenditures per credit hour (the costs) are much higher. Those need to be examined, as I'm sure they are being, for whether the quality produced justifies those numbers. At the same time, the data indicate some very productive areas-- such as law-- where faculty are clearly doing more work at a lower cost. This is a good step for Madison, and hopefully leads to more such conversations--with significant faculty involvement.

Lately our attention has been drawn to one particular trend in higher education-- the disinvestment of the state from higher education. Let me add to that three others: (1) time-to-degree is up at the majority of public colleges and universities, (2) socioeconomic gaps in college completion rates are stagnant, and (3) most students are not registering any learning gains over four years of college attendance.

So while students and their families are being asked to pay more for college, it seems like they aren't actually getting anything additional for their money. That means productivity is declining, pure and simple. The fact that a college degree still brings a large wage premium is nice, but that appears at least partly (or even largely) attributable to employers' willingness to accept a diploma as a proxy for learning. Too bad for many universities: researchers are blowing apart that assumption as we speak.

But fear not: improving productivity does not mean reducing quality. Anyone who claims otherwise is ignoring the latest learning science studies. And lest you think that I'm pushing an agenda that aims to demolish the traditional institutions in favor of for-profit models, well, ask around-- nothing could be further from the truth. I focus on enhancing productivity because making gains in this domain is truly the only politically viable way of making opportunity affordable.

High-caliber institutions like Carnegie Mellon are pursuing new ways to educate and support undergraduates that are more productive-- and thus more cost-effective-- than older models. Some colleges and universities feel threatened by this, and loudly proclaim their current practices "work" and are "cheaper." But the culture of evidence in higher education administration is notoriously weak, and thus program impacts are rarely if ever measured in meaningful ways. Absent an approach that considers impacts relative to costs, there's no basis for protecting "business-as-usual."

With that in mind, I'm going to begin to quickly highlight on this blog some key initiatives that appear to be cost-effective, highly impactful ways of educating the kinds of students like those UW-Madison serves. If the basic idea of each intrigues you, I'm giving you links to read more. My intent is to get a serious conversation started-- a conversation about refocusing on our core mission: providing a high-quality affordable education to the Wisconsin residents we serve. (We'd join many other states in this important conversation, for example read about Oregon.)

Initiative #1: Open Learning Initiative at Carnegie Mellon.

Students need effective instruction that incorporates regular assessment and supplements with tutoring as needed. Technology can assist professors in accomplishing this.

"OLI courses are developed by teams composed of faculty, learning scientists, human-computer interaction experts, and software engineers in order to make the best use of multidisciplinary knowledge for designing effective learning environments. The OLI design team articulates an initial set of student-centered, measurable learning objectives and designs the instructional environment to support students in achieving them.The instructional activities in OLI courses contain small amounts of explanatory text and many activities that capitalize on the computer's capability to display digital images and simulations and to promote interaction. Many of the courses also include virtual lab environments that encourage flexible and authentic exploration. Perhaps the most salient feature of OLI course design is the embedding of quasi-intelligent tutors—or “mini-tutors”—within the learning activities throughout the course... An intelligent tutor is a computerized learning environment whose design is based on cognitive principles and whose interaction with students is like those of a human tutor—making comments when students err, answering questions about what to do next, and maintaining a low profile when they are performing well. This approach differs from traditional computer-aided instruction, which gives didactic feedback to students on their final answers; the OLI tutors provide context-specific assistance throughout the problem-solving process."

Read more about OLI in a White House commissioned paper here.

Initiative #2: Inside Track

Persisting in college does not equate with making timely progress towards a degree, or even enjoying the academic experience at all. Mentoring can help. The Inside Track student coaching model assigns an executive coach to needy students, at a cost of just $500 for 6 months. It is an increasingly popular program at public universities, including Florida State. An extensive randomized evaluation indicates a 10-15 percentage point increase in retention rates.

POSTSCRIPT:

It's worth noting that UW-Madison has begun participating in the Delaware Study of Instructional Costs and Productivity. This allows us to benchmark instructional spending at the department level against those at other participating institutions (e.g. Ohio State University, SUNY - University at Buffalo, University of Arizona, University of Colorado - Boulder, University of Kansas, University of Missouri - Columbia , University of Nebraska - Lincoln, University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill, University of Oregon ,University of Texas at Austin). (These aren't the best comparisons but they are all that's given, and at least one of my readers is demanding comparisons no matter what.) The most recent year of our data indicates that our direct instructional expenditures per student credit hour are on the high side--not appalling high, but higher than average-- and importantly that there is widespread variation by discipline and department. Of possible concern are departments where the number of student credit hours per instructional faculty (e.g. the volume) is much lower than that of the comparison group of institutions, while the expenditures per credit hour (the costs) are much higher. Those need to be examined, as I'm sure they are being, for whether the quality produced justifies those numbers. At the same time, the data indicate some very productive areas-- such as law-- where faculty are clearly doing more work at a lower cost. This is a good step for Madison, and hopefully leads to more such conversations--with significant faculty involvement.

What's the Matter with Koch U?

There's much ado in Madison today about the news that the Koch Bros. made a $1.5 million gift to the economics department at Florida State University accompanied by numerous strings, including significant power over faculty hiring.

Over at Sifting and Winnowing, professors and students are debating whether or not we should be concerned about this event given the potential the New Badger Partnership creates for changing the rules of the game at Madison in ways that could increase authority of a governor-appointed board to make such decisions based on pure economics.

One writer, "Patrick," contends that the FSU incident is no big deal, because "I was under the impression this kind of thing has been going on basically forever in one form or another no matter where the funding comes from. Maybe attaching explicit strings to funding like this is a bit more open than usual, but I don’t understand how it’s any different."

To some extent, Patrick is right: donors often have conditions. In particular, they have interests in specific kinds of work, methodologies, and expertise. But faculty have conditions and obligations too. For example, at UW-Madison right now:

(1) Faculty are protected from pressure to accept every dollar offered by being paid reasonably well by their institution. That includes time for research. Sure, we still feel a desire (in some disciplines) to raise summer money and money to buy out of teaching and money for assistants and supplies-- but the fact that our base salary rarely depends on external funds helps reduce that pressure. In fact, no matter how much external money we raise our base salary is not enhanced by that money (unless it gets us a raise, which I'm told is rare) and it (supposedly) doesn't affect our chances for tenure.

(2) Faculty are further protected by obligations to disclose funders to Institutional Research Boards and on "outside activities" reports. We are asked about potential conflicts of interest.

(3) Faculty are protected by shared governance. No donor can interfere in hiring or tenure as long as that stands.

(4) Faculty are further obligated by a community which (currently) has a strong norms that uphold consideration of ethics and values in decisions about funding. As the professors said in the Campus Connection piece, this wouldn't happen at UW-Madison-- at least right now.

Those protections are crucial, for what they do is minimize the potential consequences of "academic capitalism." That term, according to UW-Madison alum and scholar Sheila Slaughter and her co-authors, means "market and market-like behaviors on the part of universities and faculty.”

The risks of academic capitalism at public research universities include a move "away from “access” (for students who are not employed and do not have easy access to good jobs) towards “accessibility” (benefiting the already employed)....this reverse[s] a pattern established over most of the 20th century: a push to increase access for low-income and minority student populations. Interestingly, academic capitalism in the new economy involves the pursuit not of mass markets, but of various privileged, niche student markets, with the effect being to change one of the basic functions of most higher education institutions in the U.S."

UW-Madison seems increasingly vulnerable to academic capitalism: despite its high rankings it is clearly still on a quest for legitimacy, strongly inclined to try and enhance revenue flows rather than reduce dependency on resources, and seemingly quite open to embracing the influence of globalization. Frankly, it's a prime target for donors with agendas-- but right now, there is a substantial palace guard protecting us. Dismantle that guard-- as I think the NBP with its new Walker-appointed board and focus on private fundraising will-- and watch the chips fall.

Think I'm exaggerating? Here's the report on a top Walker cabinet member, Department of Administration Secretary Mike Huebsch, on the NBP (hey thanks Vince Sweeney for pointing this one out!):

"Speaking in Brookfield Wednesday at a gathering of the Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce, he [Huebsch] told the group it would bring a free-market approach to the university system similar to that of a corporate business..."

UW-Madison -- the new Koch U?

********

This is depressing, so let me end instead on an alterative vision proffered by Slaughter and Rhodes:

"We believe that in place of these policies, faculty and their associations and unions should reprioritize the democratic and educational functions of the academy, in addition to the local economic roles in community development that colleges and universities can play. They should systematically challenge the privilege and success of the private-sector economy that is being mirrored in higher education today, subjecting the increased investment in entrepreneurial ventures to more public discussion and more public accountability. After all, as with the dot.coms in the private sector, much academic capitalism ends up losing revenue and cost shifting to the consumer—in higher education in the form of higher tuitions. We believe that faculty and their associations and unions should redirect attention to just who exactly is benefiting from certain forms and patterns of higher education provision, and in doing so emphasize the importance—particularly during a time in which some states are realizing a new majority population—of expanding educational opportunity for those who have historically encountered social, economic and cultural barriers to entry. In the face of academic capitalism in the new economy, academics and their associations and unions should consider their own participation in this process and begin to articulate new, viable, alternative, paths for colleges, universities and academics to pursue."

Reforming Wisconsin Public Higher Education: Part 2

Here's perhaps the only thing I like about the New Badger Partnership: it's got people talking about reforming public higher education in Wisconsin.

The downside is that the terms of the conversation are constrained by its leadership: right now it's a conversation about how a single, expensive institution can continue to have lots of money to do its work. The state needs to transform this into a broader conversation about creating a more sustainable model with which to provide public higher education to all state residents.

That requires far more than a few "flexibilities" or the creation of yet another governing board. There are fundamental issues we have neglected to tackle for far too long. And these issues make university administrators and faculty members very uncomfortable, for they strike at the core of the enterprise. The trick is how to "strike" at the core in a way that transforms it into something better, rather than something awful.

Here are big questions we must begin to consider and address if the overarching goal of sustaining a public higher education model in the state will be met:

(1) How can we best increase institutional performance on several metrics related to undergraduate and graduate education?

(2) How can we tie some of the funding for higher education to performance? (Right now we pay for "butts in seats" not completed credentials)

(3) How can we best assess duplicate or similar programs that could be meaningfully consolidated?

(4) Are there too many public higher education institutions in the state?

(5) Are all senior administrator positions adding value? What about all professors?

(6) Are all degree programs at each institution adding value?

The downside is that the terms of the conversation are constrained by its leadership: right now it's a conversation about how a single, expensive institution can continue to have lots of money to do its work. The state needs to transform this into a broader conversation about creating a more sustainable model with which to provide public higher education to all state residents.

That requires far more than a few "flexibilities" or the creation of yet another governing board. There are fundamental issues we have neglected to tackle for far too long. And these issues make university administrators and faculty members very uncomfortable, for they strike at the core of the enterprise. The trick is how to "strike" at the core in a way that transforms it into something better, rather than something awful.

Here are big questions we must begin to consider and address if the overarching goal of sustaining a public higher education model in the state will be met:

(1) How can we best increase institutional performance on several metrics related to undergraduate and graduate education?

(2) How can we tie some of the funding for higher education to performance? (Right now we pay for "butts in seats" not completed credentials)

(3) How can we best assess duplicate or similar programs that could be meaningfully consolidated?

(4) Are there too many public higher education institutions in the state?

(5) Are all senior administrator positions adding value? What about all professors?

(6) Are all degree programs at each institution adding value?

What the NBP Really Costs

UW-Madison is a rock star. Look at how we stack up in nearly every ranking imaginable! It is a public Ivy, and there is no objective indication that the model that built this institution has stopped working, causing a consistent downward slide. Indeed, its own press office notes that it "continues to be lauded" and the Badger Herald reports the same from key members of the Administration.

Now consider this: For the last 18+ months, University Administration has spent an enormous amount of time trying to change the way UW-Madison is governed and financed. They've pushed a plan that includes no specific, demonstrable cost savings. And their efforts have consumed enormous resources, including but not limited to a preponderance of the time and attention of all Bascom Hall leaders (at least 10-12 people, if not more), their staff, deans and other administrators, faculty from across campus, and graduate and undergraduate students. Plus all of those media resources (town hall meetings, flyering, computing time, etc). Not to mention the resources spent by our alumni on the Badger Advocates and the WAA's robocalls promoting the NBP.

And for what? All that money spent to promote a plan without a single demonstrable $ savings attached to it? And now, rumors that instead of "money-saving" flexibilities we are going to get not one but two new governing boards?

I've said it before, and I'll say it again-- a hard look at this plan indicates that it's not about money, it's about power.

My crystal ball says the first thing to go is shared governance. It is undoubtedly inefficient. And many of those in charge give us every reason to think they don't truly believe in it.

The big question is this: Do you? What are you willing to do to protect it?

Or perhaps, instead, you'll welcome a shift to professor accountability, such as that being implemented at public universities which lack shared governance.

Now consider this: For the last 18+ months, University Administration has spent an enormous amount of time trying to change the way UW-Madison is governed and financed. They've pushed a plan that includes no specific, demonstrable cost savings. And their efforts have consumed enormous resources, including but not limited to a preponderance of the time and attention of all Bascom Hall leaders (at least 10-12 people, if not more), their staff, deans and other administrators, faculty from across campus, and graduate and undergraduate students. Plus all of those media resources (town hall meetings, flyering, computing time, etc). Not to mention the resources spent by our alumni on the Badger Advocates and the WAA's robocalls promoting the NBP.

And for what? All that money spent to promote a plan without a single demonstrable $ savings attached to it? And now, rumors that instead of "money-saving" flexibilities we are going to get not one but two new governing boards?

I've said it before, and I'll say it again-- a hard look at this plan indicates that it's not about money, it's about power.

My crystal ball says the first thing to go is shared governance. It is undoubtedly inefficient. And many of those in charge give us every reason to think they don't truly believe in it.

The big question is this: Do you? What are you willing to do to protect it?

Or perhaps, instead, you'll welcome a shift to professor accountability, such as that being implemented at public universities which lack shared governance.

UW-Madison is Elite, But it Doesn't Have to be Elitist

Several critics of the New Badger Partnership contend that the policy will accelerate the development of UW-Madison as an elitist institution. In response, proponents of the policy ask "what's wrong with being elite? Madison is elite."

Both are right. The words "elite" and "elitist" mean different things.

Many people are clearly confused about the difference. In a discussing a column by a UW-Madison alum concerned about his alma mater's latest moves,"badgertom" writes "You call UW-Madison elitist. But clearly they are the very best."'

As recent events have starkly highlighted, Madison is both elite and elitist. The first is a good thing--it means that Madison is a objectively a top performer, excellent in many ways. The second is not-so-good, since it means that Madison is exclusionary, focusing on preserving its own privileges at the expense of others.

I think evidence of both abounds, but unfortunately much of the rhetoric coming from Madison's leaders these days emphasizes the elitist approach the flagship is taking to deliver an elite education.

To wit:

(1) Multiple administrators have claimed that the flagship is hindered by its relations to other universities, even "shackled," and instead must be "freed." More importantly, while some claim that no harm will be done to other universities, others claim "Not our fault if they are hurt." They seem to have no capacity to imagine ways to remain strong and excellent without outcompeting others (see the graphic...)

(2) Chancellor Martin has claimed that those who oppose the plan have not done their homework ("You need to get your data and you need to get it right"); else they would get on board. She has also dismissed students' concerns that the debate has engaged some and not others, disenfranchising the less powerful members of Madison's community. Other proponents of the NBP do the same, putting down critics as "not so able." Making people look or feel silly for highlighting power dynamics is a common tactic of elitists.

(3) In their most honest moments, some NBP proponents have admitted that if access and quality must be traded off, they will pick a "higher quality" institution that is less accessible -- supposedly necessitating the exclusion of some. The third option-- improving productivity, thus making high quality opportunities affordable--is ignored.

(4) Administrators have insisted on using elitist language--specifically, short repetitive words and phrases like "tools" and "flexibilities" and simple syntax-- as a form of controlling the terms of debate. This is not language that encourages an inclusive policy debate but rather one that serves to protect the powerful. Don't believe me? A recent email from Bascom told some members of the UW community: "When I spoke briefly with all of you... on April 27, I asked that one of your key talking points moving forward should be a consistent mention of momentum. With each passing day, support for NBP is growing stronger on and off campus, and we need to make sure we make note of that." And lo and behold, Chancellor Martin's most recent missive to her constituents says, "Lawmakers are just beginning to focus on the higher-education portion of the budget and as we continue to make our case at the Capitol and in the community, we are gaining momentum."

To sum: those that are claiming Madison is acting elitist are not claiming it should not be an elite institution (contrary to what "mikeylikesit" says). But sadly, those pushing the NBP have employed a highly elitist process and elitist rhetoric in an effort to keep UW-Madison elite.

Who Should Pay for Public Higher Education? Who Will?

On the subject of public higher education, with whom do you agree?

Person A: "Since most of the financial benefits of college go to the student, he or she should pay a large portion of college costs. Even with the large tuition increase, [our tuition is] well below those of many other prestigious flagship public universities. The ... bureaucracy is bloated, teaching loads are low, and most of the budget goes for noninstructional expenses. Most attendees come from moderately to very prosperous families that can shoulder this extra burden. Lower income students are largely protected by ...financial aid policies and by an increasingly generous federal student assistance program."

Person B: "The budget situation facing the university... is truly dire. It’s been a long time coming, and while they could have done more to restructure costs to reduce what they now will get from students, no amount of resource planning could have forestalled a crisis at this level. That said, retroactive finger-pointing at the Regents and the administrators isn’t going to solve anything. Strong public universities can survive bad government for a while, but eventually the wheels start to come off. They’re the people who’ve got the job to right this ship, and I hope they will. The bigger problem is with state government, as the lion’s share of the responsibility has to lie with the legislature and Governor, who for decades have been presiding over the erosion of public investments in higher education, while they’re jacking up spending on prisons and the state share of Medicaid. Like it or not, government officials are the investment managers of the portfolio that will pay for our collective future. Too many people seem to think it’s possible to insulate public institutions from the consequences of dysfunctional government. It doesn’t work that way: strong institutions can survive bad government for a while, but eventually the wheels start to come off."

Person C: "For decades states have been unable to provide public research universities with the levels of financial support they need to prosper, and our nation’s current economic problems have dug the holes that they face even deeper...The real danger is that higher tuition levels may lead to decreased public support. Increasingly tuition increases must provide the resources to offset limited increases, or decreases, in state support. To maintain their accessibility to students from all socioeconomic backgrounds, the great public research universities have developed institutional financial aid programs, and they need to annually demonstrate to state government that these programs are working...The real danger from [a tuition] increase is that unless the public can be educated about the great bargain that attending the university...remains, its higher tuition levels may lead to decreased public support for enhanced state funding in the future and thus to a continuous cycle of large tuition increases. Furthermore, absent the large endowments and flows of annual giving that many public research universities have, public comprehensive universities and two-year colleges will not have the institutional financial aid resources to move to a high tuition-high aid policy. Large tuition increases at the public comprehensives and the two-year colleges have the real potential to reduce access, and state governments need to understand the importance of state support to prevent this from happening."

Sound familiar?

Surprise: none of these folks was talking about UW-Madison. All three were speaking of the University of California's crisis back in 2009.

One of the dominant trends in higher education over the last 30-40 years is the rapid shifting of the costs of public higher education from the shoulders of the government onto the backs of students and their families. Many but not all see this as a problem (those that do not tend to underestimate the public returns to higher education and overemphasize the private). And people disagree over the solution.